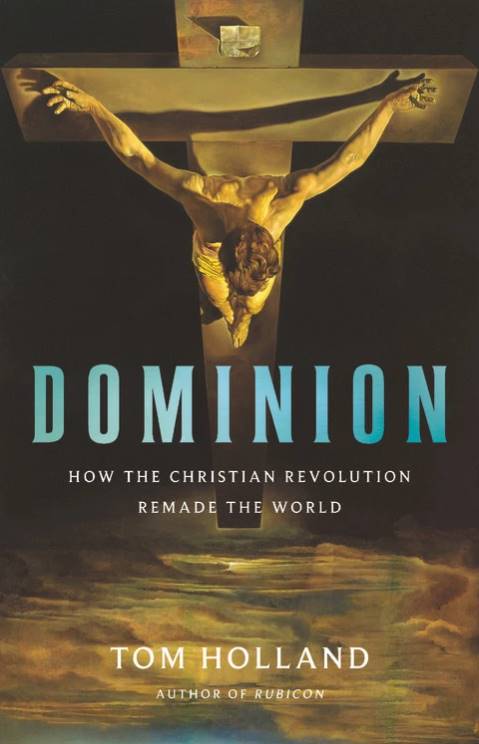

Amid the other books of Tom Holland, the book Dominion is a remarkable book. In other books he is often the skeptical contemplative academic, even if he is nevertheless a strong storyteller. However, this book is not only interesting, but it also has a message. He tells how the message of the Christian faith has changed the world.

A different Tom Holland

But in order to be able to tell that story, he first had to go through a change himself. He tells about it in the introduction and in the epilogue. Although he had already departed from the faith of his childhood, when he visited the Middle East, at the front, during the time of Islamic State, and saw and heard of the crucifixions they had carried out and the selling of women and children like slaves he got a different view of history. The Christian faith has changed society, public morals, manners. Not that no major crimes have been committed within the Christian world and by Christian civilization itself. But both with naming the achievements and criticizing the crimes – we actually are participating precisely in the tradition of Christianity itself, according to Tom Holland.

It is therefore not surprising that Tom Holland starts his book with the meaning of the cross as punishment and as a fearsome threat to slaves. That was already the case with the Persians. In a society of 90% slaves, such as the Roman Empire, it is the way to frighten and keep the slaves calm. In that world the church, Paul especially, comes with the message of faith in the crucified Christ as a new way of life. This belief involved an intensive form of charity that was unusual in society at the time. Taking care of foundlings, burying the dead, who often were left unburied and disposed as garbage if they were poor, sharing of food. The Roman Empire increasingly found these forms of charity in opposition to it, firmly organized. Many martyrs, especially those of the highest rank, who had become Christians, but also ordinary soldiers, were willing to suffer death and persecution.

Wherever this belief went it instituted a new morality, and it also influenced the Western European tribes, while at the same time this belief was attractive to the leaders of these tribes, as a moral power that legitimized their authority not only over their own tribe, but also over other tribes. Once their rule had been supported by the authority of Christ and the Church, it gained in credibility, but in turn this was also due to the fact that, according to that same belief, they could no longer serve merely their self-interests.

A broader perspective

The book provides many stories that actually require to be understood within the broader perspective of Western history. For those who do not see that thread, the storyline of the book becomes somewhat anecdotal, because Tom Holland does not always, usually not, provide that broader perspective. Why are there martyrs, and saints, who even spend that time sitting on a pillar in the desert sometimes? At another time there are revolutionaries, such as the Albigensians and the Hussites, who take up arms not only against the worldly powers but also against the church. Why? Certainly, he wants to point out the ambivalence of Western and Christian history and he does so throughout the book. The Christian faith has been used to justify power and control, as much as to justify opposition to it. But he leaves the question open, why at different times people also face different challenges. Hermits and saints who lived in the desert were needed to convince the people that the power of the demons had been broken. But once that is successful, new tasks emerge. The world now abandoned by the demons must be ordered and organized. That is almost an unavoidable next step. These kinds of insights are missing in the book.

Secularization is internalization

Nevertheless, there are two important points he makes. The first is particularly evident at the beginning of the book, and I just described it: Christianity and its morals have made sure that we finally (hopefully) departed from the violence and horrors of ancient times (and their religious legitimation!). That is one.

The other is his view of the post-Christian secularized world and morality that is now prevalent. It has been introduced since the French Revolution, step by step. We leave the Christian faith and its morals behind us, we are beyond them – at least our culture is to a large degree committed to that conviction. But is that really the case? If enlightenment puts rationality in the place of faith and proclaims human rights, is that a departure from Christianity, or a continuation of it? If Lenin and the communists impose a strict regime of scientific socialism and planning economy on society, does his revolution not breathe the same spirit as the revolution of the pope against the emperor in the Middle Ages? In both cases a cynical power game takes place in which all means are permitted to achieve the (good) goal, that from now on things since we really take a different shape. Christian spirit? Such questions are asked by Tom Holland and he does not get tired from pointing out how, in secularized form and despite the explicit rejection, the achievements of the Christian era are also continued by the greatest atheists. He mentions the #MeToo movement as a final example at the end of his book. Apparently we have a culture in which the brakes on public morality have been released, such as monogamous marriage and lifelong loyalty, but under the label of self-determination and women’s rights, the puritan morality of inner self-restraint and respect for the other still returns.

Should the Christian faith step out of its shadow?

A beautiful and important insight from Tom Holland lies in a single comment he makes almost in passing. Earlier in the book, he pointed out that in the abolition of slavery, western politicians and religious leaders deliberately pointed to innate human rights as a motivation, and not to the Christian belief that was really behind it. In this way, according to Tom Holland, with respect for the Islamic religion (the Quran unambiguously allows slavery and Mohammed himself had slaves), or Hinduism, one could prevent others from feeling they had to bow to Christian values. The end of slavery was not motivated by Christian values, but on the grounds of a generally valid human nature. It was better to keep the Christian motivation anonymous. Now the situation may look a bit different. Almost casually, Tom Holland notes that a rethinking of Western European history stamped by Christianity is now necessary as we are about to see other superpowers take over the leading role in world history. Again, Tom Holland only mentions that in passing, but it may nevertheless be an important message from his book. Indeed, in order to keep the modern world of states from falling back into pre-Christian times, it is more necessary to recall the way in which we got where we are now. The neoliberal adage of everyone for himself and the market for us all is slowly coming to an end. Too many people are offside. Neo-liberalism ignores the deeper values that are the secret of Western democracies. Those values are not so obvious. They have been introduced into society through the Christian faith, through Jesus, Paul, Peter and the other apostles. The Christian attitude towards to life is the supporting force and the lasting inspiration behind it. And it will remain so, as long as people feel the need to see the world through the eyes of the victims, and powers that be through the eyes of the underlying, and as long as ordinary people create forms of cooperation independent of family and state, in order to give to society a more human face. This history still sets the normative standards for the future.

Tom Holland, Dominion, The making of the Western Mind, Little, Brown, 2019.