…and cross-cultural entrepreneurship

…and cross-cultural entrepreneurship

Why do many development projects in the South fail? Why is entrepreneurship so difficult to get off the ground? Why is the level of production low in Africa? In addition to mining and some agricultural products, not much is exported. African companies that do produce often target external markets rather than their own. Why? The African elite often prefer to invest outside Africa. Why? It is due to the social structure of African societies. Two systems are at odds with each other and influence each other in complicated ways. They often evoke precisely the wrong reactions from each other rather than complementing each other and learning from each other. On the one hand, there is the traditional system of lifelong solidarity with family and close friends and vertical clientelistic networks that extend into the administration. On the other hand, there is the modern system of rule of law, and open networks. This is not only the case in African countries (in different versions and degrees), but in many more parts of the world. But it is very much present in Africa. If we look at history with a large telescope, the background of it also becomes visible: in the vast emptiness of Africa, it was not really possible (except along the Nile) to establish sustainable hierarchical imperial cultures. There have been many attempts, but unlike in China and India, they have been unable to sustain themselves continuously. That is why society in Africa has usually remained small-scale, and in such a society the clan and the tribe provided all that was needed for cooperation and survival. That tight-knit village society has often been destroyed by Western influence, while a Western system with its typical division of roles between state and civil society is also not really getting off the ground. As a consequence, African countries often experience the worst of two societal systems.

Typical situation of a development project

What applies to a development project is often also the case with cooperation between companies from the West and in Africa. If there is money for a project or for a start-up company, a plan is made for the next three or four years. The company in Africa is supported with knowledge and expertise from the Netherlands (for example). African staff members are recruited and the business strategy is outlined. One can try to start big in order to make an impact. Often small initiatives are supported in the hope that a small company can grow. If capacity building would only be about knowledge and skills, then that wouldn’t be a problem. But there is a difference between knowing and realizing. There is a difference between having the knowledge and also believing in what you know. An entrepreneur often needs to know something about many different things and be able to switch quickly and play on different fields. A farmer for instance must understand something of chemistry in order to use the right fertilizers or pesticides. However, the same farmer must also understand people. And he has to respond to the market. The farmer is constantly at the crossroads and is pulled at from all sides.

On top of that an entrepreneur in a developing country also has to deal with a completely different society. This societal context also influences the perception of each other. The western and the non-western partner therefore perceive each other in different ways. The Western partner is always looking for a… partner. I already used the word automatically. The word partner means that you are looking for someone on an equal level with whom to cooperate in mutual responsibility and independent commitment. Let the Dutch partner be the strongest at the beginning, no problem, over time the non-Western partner must take over the project or company and continue independently. That’s the idea.

But often the non-western “partner” has a different perception. If he or she is part of a country where vertical networks and patronage are indispensable to get things done, she or he is inevitably looking for an umbrella for protection. This is how society works from high to low, and from left to right. If you cannot mobilize someone higher up in the hierarchy to arrange a permit, or to get rid of an unfair fine and so on, the company will not get off the ground for lack of protection, possibly also by outright opposition . Project partners from such a society will consider the Western party as a “partner”, but rather as an alternative umbrella. Someone with that perception often adopts the attitude of “just tell me what I should do.” After all, the other has the money and the power and knows how to get things moving. If this “partner” asks you what you actually want, you might take it just as a courtesy.

Due to this different perception, there are problems with the devolvement of the project. In the end, the Western partner wants the non-Western partner to continue independently with the company or project. All conditions may be fulfilled; the project or company could become self-sufficient, and all knowledge has been transferred. And initially indeed, the non-Western partner takes over, but after a while the project falls into disrepair. And the Western partner gets the feeling that the African partner is not on top of it and is not doing what he should have learned over the years. In this observation of the Western partner, it is first of all overlooked that learning is not only a transfer of information, but that it also requires a change of attitude: good planning of many different things, taking initiatives, consultation of many parties, continuous innovation and new knowledge, ensuring that there is a good team and so on and so forth. All of this belongs to the concept of capacity. These are not automatically the qualities of the traditional African family business. Secondly, and that is what is especially important in this context, the Western partner has not noticed that he functioned as an umbrella for the non-Western partner. Where the Western partner thinks in terms of partnership and transfer, the non-Western party suddenly sees its protective umbrella taken away. He or she will have to look for another umbrella sooner or later. Because without a vertical network of solidarity and dependence you often can’t make it, especially in African countries, but often also elsewhere.

Mapping the different social structure

Why is it often necessary in African countries (and elsewhere) to have a vertical network and an umbrella above you? Once more a large historical telescope is required to see details that would otherwise escape one’s attention. The main social unit has always been and still is the family, or the clan. Around it you can draw wider circles: village, tribe, language, religion, and so on. As a result, there is not much public trust and no public space of mutual responsibility, no civil society. The group you belong to and especially important members of that group, should arrange things for you. In India that is often still in the hands of the castes. In Africa, this function is fulfilled by the vertical networks of important clan chiefs, or regional politicians of the same tribe or region or religion. One always needs a “we group” with a rather indifferent attitude towards the rest. It is easy to adopt an indifferent attitude towards people outside your family or group or network. There is no moral bond with other groups, who are considered outsiders. And if someone from another vertical network has to arrange something for you, maybe a friend of yours will have access to that network, and for a “fee”, things will start moving, either a license or a signature for the approval of imports, and so on.

This also has consequences for the functioning of the government, because there is no level playing field. Everything is dependent on personal contacts and privileged relations. For example, companies affiliated with politicians can obtain exclusive rights to mines or exports, for which they must of course also reciprocate, etc. Transparency, equality before the law, an independent judiciary, everywhere they lead a difficult life. It is present, but it is constantly overruled by the vertical networks mentioned. Often this is also a way for politicians to buy trust and cooperation from parties that might otherwise oppose and obstruct them. For example, if Ghana (2020) has 120 ministers in the cabinet, it is not because there is so much work, but because all kinds of groups, regions, religions, must have their influence and their share. One can imagine how difficult it must be to have well-functioning infrastructure, educational policies, agricultural policies, etc.… across the country. Such a policy must constantly deal with or crash on vertical networks with their own agendas.

Corruption?

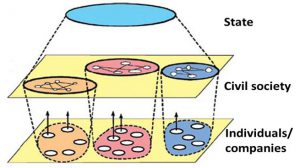

Western parties dealing with the aforementioned problems are too quick to use the word corruption. After all, if there is not a civil society with anonymous trust, give and take, under the protective umbrella of transparency, rule of law, contract enforcement, and so on, what else can people do but “buying” trust from each other, in return for cooperation. What else can they do but join the group they belong to, and seek protection from of an important “big” man at the top to secure their interests? So it is rather an institutional problem and the problem of social codes instead of private behavior. In addition, the entrepreneur in the example above may have a salary from a Dutch project for four years, but if the project or his business fails, he still has to fall back on his family or other important people in the vertical network. If he has not maintained those relationships well in times of prosperity, he in turn can expect problems in times of adversity. Instead of corruption, it is better to speak of two different systems. My proposal is to map those two systems in the following way.

System I and System II

| System I | System II | |||

| Institutions | Values | Institutions | Values | |

| State | Patrimonialism at the top, granting favors and privileges in return for services | Obedience and loyalty, hierarchy, status, personalized relationships, particularism | Rule of law, equal access, strong but accountable state institutions, property protection, contract enforcement | Universalism, equal access, justice, transparency |

| Civil society | Closed in-groups, vertical networks, little cooperation

|

Lifelong solidarity, adaptation to the group, traditionalism, uncertainty avoidance | Civil society, open cooperation at the bottom, changing coalitions (apart from family loyalty and state authority) | Open attitude, mutual adaptation, multiple memberships, pluralism of opinions |

| Individual enterprises | Family based, distributed activities, dependent on position and opportunities in the vertical network | Command and control, status through position, closed in-group ethos, loyalty counts more than efficiency, synchronic time management, privileged treatment of in-group members | Open labor market, contracts, instrumental working relations, both of competition and cooperation between competitors | Individual judgment, professional attitude, initiative, status by achievement, planning and innovation, cooperative attitude, equal treatment, teambuilding |

In this table, System I and System II represent two ideal-typical forms of society. The first is more traditional, and fits a nomadic or agricultural community, and of a small scale. The second is modern, or new, or Western, but an abstract designation has been chosen instead, since none of those terms covers the meaning with due precision. Even the West has not really arranged everything according to System II. Nor is modernity an end point of development. There is always a new modernity. And should one then call System I “old-fashioned”? After all, this is by no means the case, because it is highly developed and refined, apart from the fact that every family is also a System I phenomenon in the West. System I is our common foundation. System II is an innovation.

In addition, the table distinguishes between institutions and values. Particular institutions are related to particular values and institutions and values reinforce each other. If the institutions are very top-down, it is obvious that a value like loyalty is very important, and so on.

Those who take a close look at the table may gain valuable insights. African countries are not unequivocally organized according to System I, but they rather are a mix of System I and System II. This means that the citizens of Africa actually live in two worlds. Citizens is actually a System II related term. But that citizenship is often thwarted by family belongingness, village belongingness, ethnicity or religion.

Of course there are also different versions of System II in the Western world, but one thing is clear: where different groups must cooperate more and effectively and live together on a large-scale, in some way there must be more cooperation (civil society) and a stronger and equitable state. If it is not possible to create more equality before the law, then different groups are forced to exercise their influence on the state by means of the group, tribe or caste. A strong and just state is therefore required to reduce the role of group loyalty and the dependence on privileged treatment in order to enable more civil society. But the reverse is also true. There must be more civil society, more cooperation, anonymous trust, public space, in order to secure a type of governance that creates equality before the law.

Every company in developing countries has to deal with both force fields and must navigate between the two systems. Instead of putting the label of corruption on all kinds of phenomena, it would be a good thing to bring up the dilemmas that people in Africa face and discuss them openly. When should one go along with sometimes unavoidable System I practices and what can one do to move towards more System II practices? Some companies already have a family fund, to name just one example. The family can appeal to the director and ask for help from that fund, thereby recognizing System I. But the fund is limited, because the family should also recognize that the company must also survive.

I have elaborated the above views in detail and with many examples and case studies in Kroesen, J. Otto, Darson, R., Ndegwah J. David, 2020. Cross-cultural Entrepreneurship and Social transformation: Innovative Capacity in the Global South, Lambert, Saarbrücken, 331pp.

The book can be found by typing / copying the title on the Internet and Researchgate, the relevant website. A direct link can also be found on the “links” page of this website.